Written by Dr. Alia Soliman

Material culture refers to the physical objects and architecture that a society, or cluster of people, use to define itself. It encompasses items from everyday tools and clothing to buildings, monuments, and even art. While tangible, material culture actually carries layers of meaning and reveals complex stories about people’s lives, values, beliefs, and history. Thus our interaction with these objects, be it in a museum space, an intimate setting, or a public square, depends on a multitude of factors that oscillate between the personal and the historical.

Several occurrences, intellectual and historical, which took place in the last few years have prompted the art and heritage world to take stock of the injustices imbedded in museum collections and cultural heritage displays around the world. These initiatives include drives for decolonisation of collections which rally around the outcry for repatriation of antiquities acquired under colonial pretexts. The wave of BLM 2020 and the COVID pandemic have forced museums to accelerate their revaluation and readjustment of their values to match twenty first century expectations and historical reckonings. In tandem, the appreciation and engagement of audience with material culture has taken a substantially more sombre, yet historically aware turn. This accountability extends to regular museum visitors and cultural heritage aficionados whose responsibility it is to be educated on matters related to cultural appropriation and the lingering effects of post-colonial discourses. Today, looking at artefacts is not (solely) about aesthetic appreciation, rather cultural engagement and a revaluation of historical processes and biases.

So how should we engage with material culture objects today?

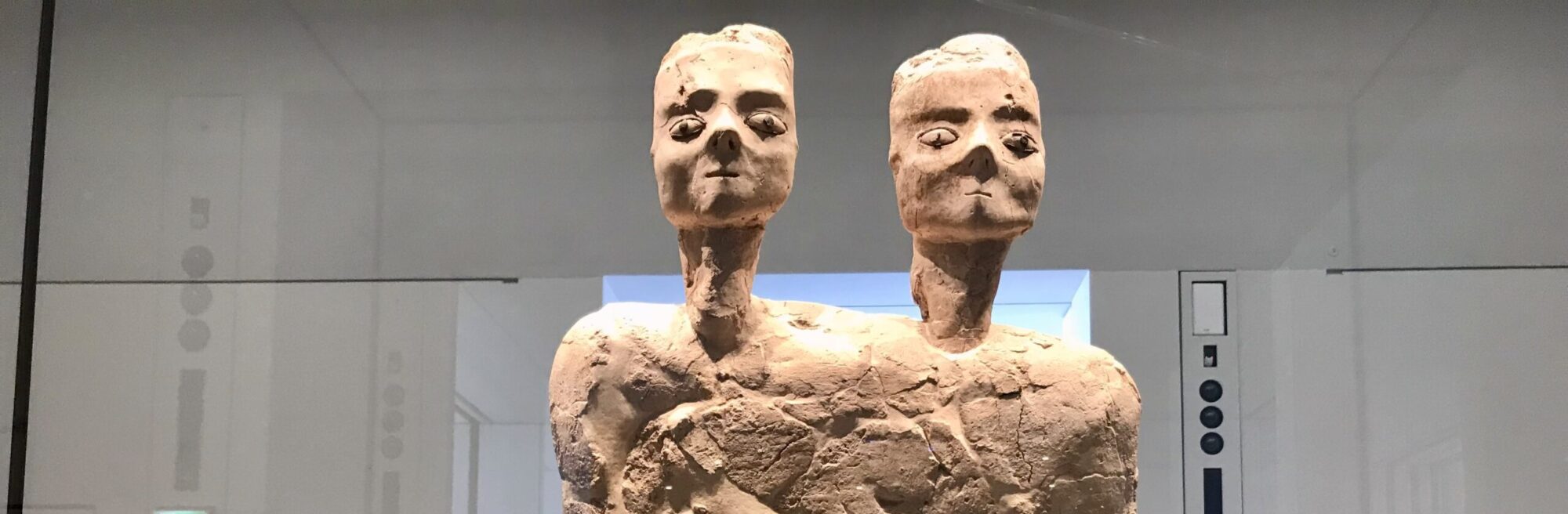

Let’s use a well-known artefact as an example.

In room 4 at the British Museum in London, sits the Rosetta Stone, a rectangular slab of black basalt, roughly inscribed with three scripts: Greek at the top, Egyptian hieroglyphs in the middle, and Demotic script at the bottom. Its surface, bears witness to the historical significance of this artefact in unlocking the mysteries of ancient Egyptian writing.

The Rosetta Stone dates back to 196 BC, it was carved during the reign of Ptolemy V Epiphanes in Memphis, Egypt. As an artefact that played a crucial role in deciphering Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Rosetta Stone allowed Egyptians to access their own cultural heritage in a way never possible before. It provided a window into their ancestors’ lives, thoughts, and achievements, fostering a sense of connection and pride. Naturally, it is considered an artefact belonging to the Egyptian culture.

Since its creation in 196 BC, the Rosetta Stone was largely untraced until the late 18th century.

In 1799, during Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign in Egypt, French soldiers stumbled upon the Rosetta Stone near the port city of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta. The Rosetta Stone became a crucial tool for linguists and historians seeking to understand hieroglyphics, a language shrouded in mystery for centuries. In 1822, French linguist Jean-François Champollion successfully deciphered the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone effectively opening the door to understanding the written records of Ancient Egypt and significantly contributing to the study of Egyptology. Champollion’s celebrated discovery came in the context of European colonialism of Egypt and the wider African continent. Champollion’s work occurred during the colonial era, and his access to Egyptian artefacts and knowledge was facilitated by European imperial powers—Champollion’s discovery contributing to the Eurocentric interpretation of the region’s history.

With Champollion’s historic discovery, the French feel a sense of ownership of this artefact as part of a broader narrative of French intellectual prowess.

With Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat in Egypt, the Rosetta Stone became part of the spoils of war, acquired by the British in 1801. Since then, it has resided in the British Museum in London, where it stands as one of the museum’s most prized possessions, a symbol of Ancient Egyptian civilisation, an essential part of the narrative put forth by a universal museum pertaining to human evolution.

As the safe-keepers of this invaluable relic, the British feel a sense of ownership of this artefact,. They perceive that the Rosetta Stone, and many other contested antiquities acquired during the Colonial Era of the British Empire, have become an integral part of British heritage, the relic having been housed in the British Museum for more than two centuries where millions of viewers from all over the world get to experience its significance within the context of other world cultures.

So who holds greater ownership, affinity, and sense of cultural belonging over the Rosetta Stone, the Egyptians who created the relic, the French who discovered its meaning and opened a pathway to a greater appreciation of Ancient Egyptian heritage worldwide, or the British who safeguard it in a world-renowned universal museum? As contested artefact, who has a greater claim to the Rosetta Stone: the culture who created it, the culture who revealed its significance for humanity, or the culture that safeguarded it and displayed it to a broader audience, placing it within the wider story of humanity?

The answer may seem clear to some and complex to others. This raises questions about ownership, cultural appropriation, and the unequal distribution of benefits from discoveries and loots made in colonial contexts. This in turn leads to a central question in the context of heritage and provenance studies:

Who owns the past?

The question of “who owns the past” in relation to artefacts is a complex and multifaceted one that has been debated by archaeologists, art historians, museum curators, and indigenous communities for decades. There are no easy answers, as the matter is often entangled with issues of cultural identity, sovereignty, and international law. Within contemporary talks of decolonisation of collections and repatriation of colonial loot, how you look at this material object will depend on your historical awareness and your stance from some of the major debates surrounding Colonial and Post-Colonial legacies.

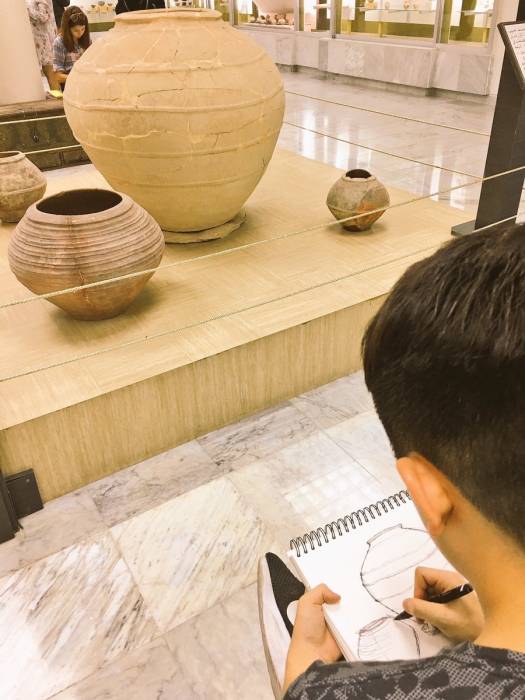

Looking at relics and antiquities in the context of heritage studies involves moving beyond simply observing their physical characteristics, although that layer is ever-present, into an understanding of the stories they tell us about the past, the people who made them, and the societies they came from but also their provenance and how many times they changed hands and through what means.

Looking at cultural artefacts starts with deliberative and attentive looking and proceeds from a registering of observations to a multitude of questions. How to navigate and approach these questions constitutes the deeper level of our engagement with these materiel culture items.

So lets stop and consider some aspects here:

1. Provenance and Ownership:

Provenance research, which delves into the origin, ownership, and history of an object, plays a crucial role in understanding the value of material culture on multiple levels. Provenance, the trajectory or the journey that the artefact has taken since its creation, including the record of ownership, is directly tied to the history of communities. Knowledge of provenance and ownership of a relic can significantly influence our perception when examining it, as it adds layers of context and meaning to the artefact. Understanding where a relic comes from and who has possessed it throughout history can shed light on its cultural significance, authenticity, and the narratives surrounding it. For instance, knowing whether an object was obtained through legitimate means or acquired through looting or theft can evoke different moral and ethical considerations. Provenance research goes beyond monetary value, enriching our understanding of an object’s cultural significance, historical context, and ethical implications. This comprehensive knowledge ultimately shapes its overall value, both tangible and intangible.

2. Material Analysis:

An examination of an artefact’s physical properties can lead to a deeper understanding of its significance, this includes its size, shape, weight, texture, and any markings or decorations. These details can offer clues about its production techniques, symbolism, and intended use. Material analysis of a relic can profoundly impact our perception when examining it, offering insights into its craftsmanship, authenticity, and historical context. Whether by employing scientific techniques or through archival scholarship, researchers can determine the age, composition, and production methods of the object, unraveling mysteries about its origins and usage. Moreover, material analysis can unveil hidden layers, repairs, or alterations made to the relic throughout its history, shedding light on its journey and the hands through which it passed. These elements enable us to establish a tangible link to the past.

3. Iconography and Symbolism:

Study the visual elements of the artefact, such as symbols, imagery, and decorations. These can provide insights into the cultural, religious, or ideological beliefs of the community.

The iconography and symbolism of an artefact wield a profound influence on our perception when observing it, as they serve as windows into the beliefs, values, and cultural contexts of the time in which it was created. They weave stories, evoke emotions, and connect us to history, tradition, and even the supernatural. Every symbol and motif embedded within the relic carries layers of meaning, often steeped in religious, mythological, or societal significance. By decoding these symbols, we gain deeper insights into the worldview and ideologies of the people who crafted or revered the relic. Additionally, the iconography may evoke emotional responses or spiritual connections, transcending temporal and cultural boundaries to resonate with viewers on a personal level. Furthermore, the evolution of symbols over time can reflect shifts in cultural paradigms, offering valuable clues about societal transformations and historical narratives. Thus, through the lens of iconography and symbolism, a relic becomes not just an object of material value but a profound testament to the human experience and the enduring power of visual language.

4. Preservation and Conservation:

Preservation and conservation efforts are essential to ensure the longevity of the artefact and its accessibility for future generations. The preservation and conservation of a relic profoundly shape our perception when observing it, as they directly influence its physical condition and aesthetic presentation. A well-preserved relic can evoke a sense of awe and authenticity, allowing viewers to connect more intimately with its historical context and cultural significance. Conversely, damage or deterioration due to neglect or improper conservation practices may detract from the relic’s impact, obscuring details and diminishing its ability to convey its intended message. Moreover, the methods employed in preservation can reveal insights into the value systems and priorities of different historical periods, as attitudes toward conservation have evolved over time. By ensuring the longevity and integrity of a relic, preservation and conservation efforts play a crucial role in safeguarding our cultural heritage for future generations, enhancing our appreciation and understanding of these antiquities.

5. Placement and Setting:

I’d like to spend some time with this point as it is central to personal and enlightened engagement with art and artefacts.

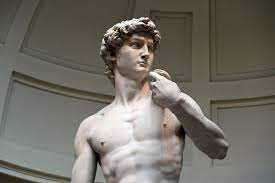

Let’s look at one of the most famous sculptures, Michelangelo’s David.

Michelangelo’s David holds profound cultural and historical significance as one of the most celebrated sculptures of the Italian Renaissance. Created between 1501 and 1504, the statue represents the biblical figure of David, the young shepherd who defeated the giant Goliath with a single stone. Beyond its religious narrative, the sculpture embodies the ideals of humanism, valor, and the potential of the individual. Standing at over 17 feet tall, Michelangelo’s David is a testament to the artist’s mastery of anatomy, proportion, and expression, showcasing the Renaissance fascination with the revival of classical aesthetics.

It would be hard to find a person, art aficionado or not, who would not be impressed by Michelangelo’s unique workmanship. In fact David been associated with a psychosomatic condition called the Stendhal Syndrome, where the viewer gets to experience a visceral psychosomatic reaction that overwhelms the senses causing dizziness and hallucinations. Looking at David, intense facial expression, the bend of the knee, the vein on his hand, each tiny detail come together to form a unique and overwhelming viewing experience.

But even this most famous artefact can be seen in a a multitude of ways. To start with the statue can be seen in two locations in the same city, and thus eliciting a different type of attention in each setting.

The real sculpture is displayed at Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze where you would be struck by its overwhelming presence as soon as you enter the relatively small hall. Crowds usually surrounding it since the gallery’s opening till its closure.

The second set stands at Piazza Della Signoria, were in 1910, the replica was created to replace the original statue. While a busy square, you can still have the statue to yourself at different times of day or night, the lighting would not be as serving for an experience immersed in visual details. However, it is a more democratic way of looking at art.

There is actually a third version that boasts different material and colour aesthetics that can be seen on the vista of Piazzale Michelangelo overlooking Florence.

So the first difference in seeing and appreciating David would be where you are experiencing it?

The second is are you able to spend a leisurely time looking at its details?

The third is how does your background, nationality, personal history, historical or religious views colour your viewing experience?

As a nude piece of art that caused recent clamour in educational circles in the US in 2022, David, as emblematic of great art as it is, it may not be appreciated by everyone.

Personal and historical context colour any immersed cultural experience.

So while the aesthetics of an object may be the first thing we notice about them, context in looking at art and artefacts is really the most defining factor.

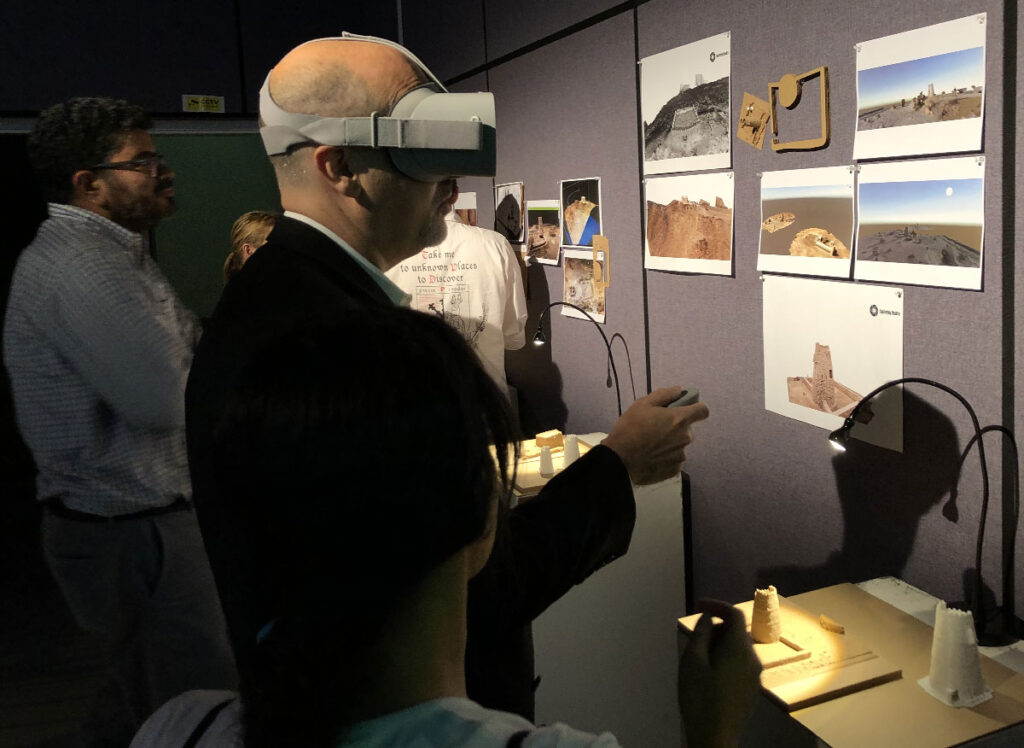

7. Digital Tools and Technological Mediation:

Digital tools have revolutionised the way we explore, study, and interact with heritage artefacts, making cultural heritage more accessible, interactive, and sustainable for future generations. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a significant catalyst for museums to accelerate their digitisation efforts. Museums faced closure and visitor restrictions, prompting them to shift focus towards online engagement and accessibility.

Digital tools and technological mediation of an artefact can profoundly influence our perception when viewing it, offering new ways to interact with and understand historical artefacts. Some of the technologies employed today in the fields of cultural heritage include virtual tours, high-resolution photography, 3D scanning which created interactive models allowing virtual exploration and analysis.

Through techniques such as 3D scanning, virtual reality, and augmented reality, material objects can be digitally recreated and explored in immersive environments, transcending physical limitations and allowing for enhanced preservation and accessibility. These digital representations enable viewers to examine the piece from multiple angles, zoom in on intricate details, and even simulate its original context or usage, fostering a deeper appreciation and understanding of its significance. Moreover, technological mediation can democratise access to relics, making them accessible to a broader audience regardless of geographical location or physical ability. These tools provide an enhanced visualisation experience and allow virtual reconstructions damaged or deteriorated artefacts of heritage sites, buildings, or artefacts in a digital environment.

The enhanced accessibility through sites and app such as Google Arts and Culture offers a “museum view” tool to look inside gallery spaces. Online tours such as the Vatican’s offer an interactive, gratuitous, and unobstructed tour of some of the world’s most ancient religious heritage objects. Further, lost and destructed heritage can be digitally recreated such as in the Mosul Cultural Museum in Iraq.

Experiencing historical artefacts is subject to a range of factors, I have outlined some of them here but a multitude of other nuanced elements can be added to this ever expanding list as humanity progresses through machine technology and human awareness.