The Politics of Heritage: On the Tension Between Official and Unofficial Narratives

All heritage is intangible. Buried under modern structures and contemporary sociopolitical dynamics at sites of cultural and historic value lie centuries of cultural traditions and practices, overshadowed today by the prestigious status of World Heritage Site (WHS). Sites like Stone Town in Zanzibar, Sultanahmet Archeology Park in Türkiye, and Ilha de Moçambique in Mozambique stand today as monuments to the cultural exchanges that took place throughout their history, at the same time that they constitute complex case studies of the dynamics between local communities and international heritage bodies like UNESCO in the context of the conservation of these sites. The tension between authorized heritage narratives and the preservation of intangible heritage is deeply embedded within heritage sites, revealing what seems to be a trade-off between the protection of intangible heritage and the maintenance of the status of a WHS, since it appears that the WHS system “flattens” the multilayered narratives that live within heritage sites and prioritizes the tangible over the intangible and the universal over the local. Can a balance ever be attained between the conservation of the tangible and the preservation of the intangible at a WHS? This analysis examined the dichotomy between authorized heritage narratives and their emphasis on tangible heritage, and community-based narratives and their intangible foundations at WHS, pushing forward the argument that, in order to preserve both the tangible and intangible aspects of heritage, institutions and local communities must achieve a balance between top-down and bottom-up approaches to the conservation and administration of the WHS. Lastly, the analysis presents the HeritageLab mapping project as a space to empower local communities and bring “unofficial” narratives into the spotlight at WHS around the world.

Since the late 1950s, UNESCO has established the intellectual framework and the legal bases on which heritage is valued and protected around the world. As established in its 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, a site becomes eligible to be inscribed on the list of WHS if it meets one of ten criteria that define its Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). In addition to the selection criteria, the 1972 Convention provided the bases for the creation of the World Heritage Committee, which works in cooperation with relevant national and international organizations and serves as the highest authority in decision-making processes concerning the management and protection of all WHS around the world.

The status that results from becoming a WHS brings several benefits for the nominating countries, including revenue from the tourism industry, the prestige that comes with international recognition, and the potential impact of the WHS status on the reinforcement of national identity narratives. Once the site is inscribed in the World Heritage List, the State recognizes the duty to protect through its own resources, following, however, the guidelines and recommendations of the Committee and associated institutions. The standardized nature of UNESCO’s selection criteria and its modus operandi as the highest authority in the cultural heritage context has triggered opposite reactions in the past decades, with some advocating for its importance in the protection and recognition of cultural sites worldwide, and others pointing at the commodification of heritage that results from its top-down approach, alienating local stakeholders from management and decision-making processes concerning the site and its surroundings.

The1972 Convention’s focus on the physical component of cultural heritage and the disfranchisement of local communities from the WHS constitute critical discussion points in the analysis of current institutional practices in the field of heritage. These issues are closely linked to the authorized heritage discourse that characterizes international heritage bodies, which, in its turn, can be traced back to nineteenth-century European architectural and archaeological scholarship centered around the protection of material culture as the only bearer of innate historic value. Authorized heritage narratives, then, prioritize the tangible at the expense of the intangible, and construct an image of the site where the dominating values and ideology belong to UNESCO rather than to the local stakeholders. In fact, the idea of local communities being key stakeholders of the WHS is not clearly defined in the 1972 Convention, flagging a limitation of the treaty as it focuses on the built component of the sites at the cost of the existing social dynamics and the development of local groups.

In response to waves of criticism in relation to the lack of emphasis on the involvement of local communities as key stakeholders and the protection of intangible cultural heritage in the 1972 Convention, UNESCO included “Communities” to the already existing Strategic Objectives of the World Heritage Convention in the 2002 Budapest Declaration on World Heritage and proposed the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003. Both initiatives aimed at targeting “weak points” and complementing the 1972 Convention as separate or additional treaties, but the original text was not edited to include the new aspects as inherent elements of the WHS system.

UNESCO defines intangible cultural heritage as the “practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage” and highlights “the interdependence of tangible and intangible heritage and the role of the youth and indigenous people in heritage maintenance”. As a case in point, following Stone Town’s nomination to become a WHS, there were significant efforts to train experts in the technical preservation of buildings and structures around the site. Records of these training initiatives do not show, however, any attempts to bridge the tangible component with the intangible narratives and traditions attached to the buildings. Most critically, the majority of the residents of Stone Town ignored the implications of the conservation works that were taking place around the site since they were not considered in the design of the refurbishment and management plans conceived by UNESCO. Not only were locals alienated from their place of residence, but Zanzibar’s storytelling traditions, culinary arts, festivities, music, dance, and typical dress, which constitute the site’s intangible heritage, were also detached from the authorized narrative presented at Stone Town, relegating them to a space of less value within the heritage discourse. In theory, UNESCO seems to agree with the stance that the intangible heritage that corresponds to living Heritage Sites holds as much OUV as historic structures do. However, the systematic exclusion of this crucial element of the heritage narrative of a living site from the priorities of international heritage institutions reveals a dichotomy between theory and practice, institutions and communities, and tangible and intangible heritage, at the same time as it highlights the need for management systems to consider narratives from the intangible heritage of local communities in the administration and conservation of the sites.

The status of a WHS has direct impact over the local tourism industry, creating new job opportunities for the local population and creating revenue for the local governments. A survey conducted in Zanzibar in 2009 found that approximately 90% of the locals considered that the reputation and the general appearance of the island had improved significantly since the tourism industry flourished, but 86% felt that more entrepreneurial activities from the community were necessary for these key stakeholders to get involved with the tourism activity in their town. While local governments encourage investment in the tourism sector at WHS, community dynamics and their engagement with their own heritage and identity are at stake, a conflicting trade-off that comes with the responsibility of maintaining the prestigious WHS status under UNESCO’s terms. To preserve a WHS’s “authentic form” that UNESCO’s authorized narrative is generally based around, or to allow the modern inhabitants to determine the evolution of these sites?

UNESCO’s attempts to highlight the role of local communities and the importance of intangible cultural heritage have fallen short to its own emphasis on material culture and top-down management systems in the 1972 Convention, the treaty which, ultimately, serves as the foundations of the WHS system. A consequence of this centralized approach to safeguarding the tangible at the expense of the intangible is the loss of public spaces that local groups face to the tourism industry. Generally, international heritage management plans lead to the repurposing of areas that were previously used by local communities in the benefit of the tourism sector, revealing the prioritization of a site’s status of WHS over local community dynamics. It becomes the role of national and local governments, then, to place local communities at a level of priority in an attempt to preserve local culture in the face of a globalized tourism industry. National and international heritage legislation, then, must work in consonance, including the involvement of local communities as key stakeholders and the protection of both the tangible and intangible elements of their cultural heritage as priorities in their agendas to balance the influence of international bodies with the dynamics of WHS. The creation of additional treaties for these purposes has proved not to be sufficient in practice if the core of the WHS system is not amended to reflect these two fundamental elements of cultural heritage in an attempt to combine top-down and bottom-up approaches to the management of the site.

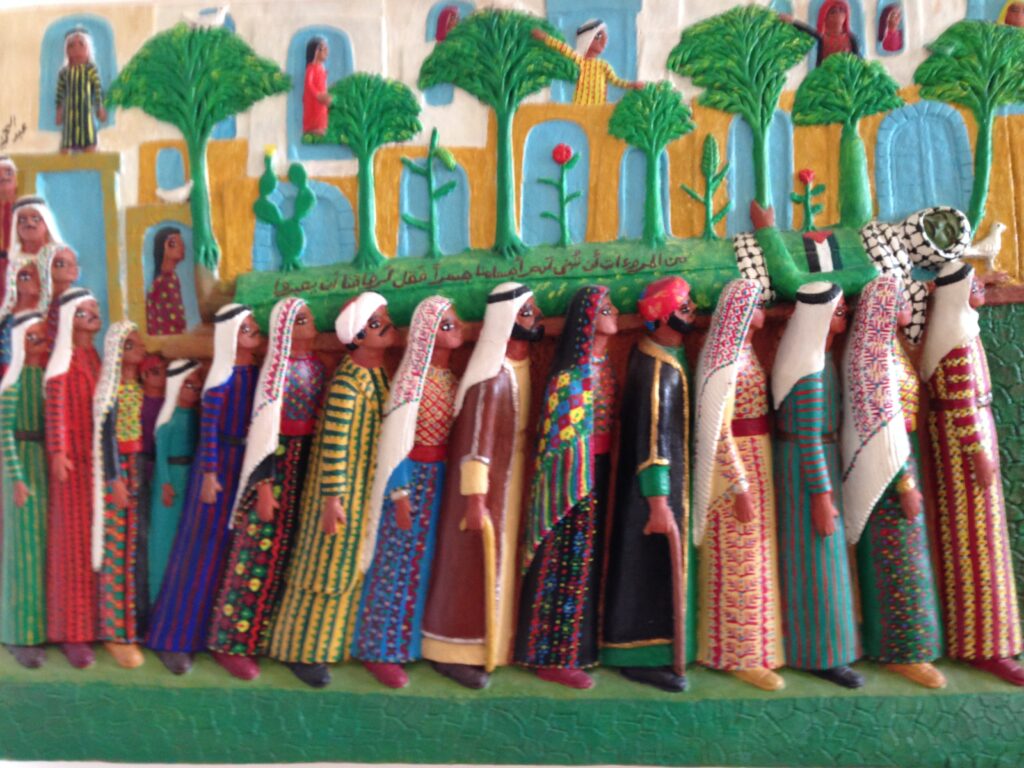

The case of Stone Town has also inspired the global community to reflect on the dichotomy that exists between tangible and intangible heritage and international heritage management and the local population. The HeritageLab mapping project, overseen by the Dhakira Center for Heritage Studies, focuses on the visualization and juxtaposition of “unofficial” narratives and the authorized heritage discourse at several WHS around the world. The project brings a diverse and multidisciplinary team of scholars and researchers together with local communities and stakeholders, with the purpose of documenting and drawing attention to the intangible heritage and community narratives that have been overshadowed by the dominating authorized narratives at the WHS. Moreover, the project explores the potential of digitizing cultural heritage in the mission to reconcile official and unofficial narratives and tangible and intangible heritage, bringing all elements into the same space and presenting them as part of one same story. The different maps that conform HeritageLab juxtapose UNESCO’s authorized heritage narratives with community interviews and stories about the traditions and the meaning of the sites for the local population. Most critically, the maps aim at showing the interaction between these two layers of heritage narratives, conveying a message of unity that reconciles international and local stakeholders and promotes the conservation of both the tangible and intangible elements of the heritage site. A unique element of the project is the collaborative and democratic nature of the maps, with local communities being granted the freedom to upload their stories directly through the website. The HeritageLab maps invite local stakeholders to take ownership of the project, which is intended to serve as an archive for communities and as a source of research material for the international audience interested in heritage beyond the authorized heritage discourse.

Not only does the complex historic, cultural, and socio political background of WHS pose a challenge for heritage management institutions, but also the importance of the local population’s intangible heritage for the overall narrative of the physical site. This analysis explored the dichotomy between UNESCO’s authorized narrative and community-based narratives in the WHS context, supporting the position that a balance must be achieved between top-down and bottom-up approaches to the conservation and administration of WHS for an inclusive, genuine, and durable approach to heritage management. UNESCO’s emphasis on tangible heritage as the pillar on which selection criteria and management plans are constructed, and the imposition of a World Heritage Committee as the highest authority ruling over all WHS, has proved counterproductive for some sites where communities continue to live and work. The maintenance of the WHS status can transform the site into a commodity for the tourism industry, alienating local communities and other key stakeholders from management and decision-making processes concerning the site. UNESCO defines the safeguarding of WHS as the process of “ensuring the viability of the intangible cultural heritage through various means”. Such means, however, will not always concern action from international heritage bodies, but might take the form of community initiatives targeted at challenging the bases of the WHS system and bringing the intangible component of heritage to the same level as the tangible element at WHS. Projects like HeritageLab seek to resurface the forgotten layers of intangible and community-based heritage that were long buried under UNESCO’s authorized heritage narrative and that are of utmost importance to the overall OUV of WHS around the world. These initiatives and their outcomes must not remain at the margins of international heritage legislation and action. They have the power to nurture authorized heritage narratives, resulting in a more robust, authentic, and inclusive perspective that englobes the material and the immaterial elements that render the site so significant for the local population and global audience. These projects aid in the process of bridging the tangible and the intangible, the official and the unofficial, and the global and the local into a fruitful dialogue, revolutionizing the understanding and application of the WHS system, and contributing with the creation of new narratives that are truly inclusive of all involved stakeholders and sustainable in the long run.

Bibliography

Boswell, Rosabelle. “Challenges to Sustaining Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Heritage & Society 4, no. 1 (2011): 119–24. https://doi.org/10.1179/hso.2011.4.1.119.

Boswell, Rosabelle. “Say What You like: Dress, Identity and Heritage in Zanzibar.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12, no. 5 (2006): 440–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250600821548.

Hitchcock, Michael. “Zanzibar Stone Town Joins the Imagined Community of World Heritage Sites.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 8, no. 2 (2002): 153–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250220143931.

Martinsson-Wallin, Helene, and Karlström, Anna. “World Heritage and Identity: Three Worlds Meet: A Workshop Arranged during the VII International Conference on Easter Island and the Pacific: Migration, Identity, and Cultural Heritage.” Semantic Scholar. (2007). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/World-Heritage-and-Identity-%253A-Three-Worlds-Meet-%253A-a-Martinsson-Wallin-Karlstr%C3%B6m/01271fbdec0c74d8a102d0d6477fc4dc34bd8324.

Okech, Roselyne N. “Socio-Cultural Impacts of Tourism on World Heritage Sites: Communities’ Perspective of Lamu (Kenya) and Zanzibar Islands.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 15, no. 3 (2010): 339–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2010.503624.

Parthesius, Robert. “Trading Places: Negotiating Place in World Heritage.” Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Management on the Historic and Arabian Trade Routes, 2020, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55837-6_1.

Sheriff, Abdul. “Zanzibar Old Town.” Essay. In The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria Jean LaViolette, 529–40. London: Routledge, 2017. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315691459-46/zanzibar-old-town-abdul-sheriff

Smith, Laurajane. “Intangible Heritage: A Challenge to the Authorised Heritage Discourse.” Ethnologia, Vol. 40, pp. 133–42. (2015). https://www.academia.edu/34518290/Intangible_Heritage_A_challenge_to_the_authorised_heritage_discourse

Turner, M., Pereira, A., and Patry, M. “Revealing the Level of Tension between Cultural Heritage and Development in World Heritage Cities.” Problems of Sustainable Development, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 23-31. (2012). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2129126.

UNESCO. “Convention concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage.” (1972). https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/.

UNESCO. “Decision 31 COM 13B: The ‘Fifth C’ for ‘Communities.’” (2002). https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/519.

UNESCO. “Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” (2003). https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention.

UNESCO. “WHC Nomination Documentation: The Stone Town of Zanzibar.” (2000). https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/173rev.pdf.

Vester, Mia. “The wall and the veil: reclaiming women’s space in a World Heritage Site.” MA Dissertation, (University of Pretoria, 2014). https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/45278.

“Zanzibar Map”. HeritageLab. (2023) https://zanzibar.heritagelab.center/category/location-page/.