Renegotiating Colonial Legacies: The Controversy around Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s Statue in Hoorn, the Netherlands

Written by Ava Abtahi

Preface

Last year, in my “Cultural Anthropology & Development Sociology” Bachelor’s, I took some courses in the minor “Cultural Memory of War and Conflict”. It combined memory studies and heritage studies, which has made me especially interested in colonial heritage, a topic I’ll explore in this article. Following the 2015 Rhodes Must Fall movement, where Cecil Rhodes’ statue was eventually removed from its pedestal at the University of Cape Town, and following George Floyd’s murder in 2020, more and more decolonial activists have been problematizing colonial legacies and heritage, particularly in the West. This has led to the toppling of several colonial figures like Edward Colston in Bristol (2020) and John A. Macdonald in Canada (2020). Since I live in the Netherlands, I want to introduce an ongoing Dutch case: Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s. It has created an intense and polarizing debate between those who oppose his monumentalization and those who support it. But before I analyze this case, who is Coen exactly?

Some Context

Born in 1587, Jan Pieterszoon Coen (see Figure 1) became the fourth Governor-General of the VOC (Dutch East Indies) in 1617. As the Netherlands competed against larger empires like Spain and Portugal, Coen helped secure a monopoly over the nutmeg spice found in the Indonesian Banda Islands, granting the economic basis for the so-called Dutch “Golden Age”. But to do this, Coen ordered the killing of the Bandanese inhabitants. Around 14,000 out of 15,000 were murdered and the few survivors were enslaved. Coen repopulated the Banda Islands with forced laborers for spice plantations. Contemporaries nicknamed him the “Butcher of Banda”.

Despite the massacre he ordered, following his death in 1629, Coen has been monumentalized and in several different ways. The most notorious example is his statue in the Northern Dutch city of Hoorn (see Figure 2), which was inaugurated in 1893, more than 200 years after he died, in the city’s main square, the Roode Steen. This contributed to the national effort at the time to honor major Dutch figures and strengthen national identity (Grever 2025).

The statue has been a polarizing and “hot topic” since Day One. Already when the monument was just a proposal, many individuals figured it was problematic to glorify someone like the “Butcher of Banda” (van Engelenhoven: 83). The debate in the 21st century centers on the tension between the role of anti-Coen activists and the “mediators” of the debate, Hoorn’s municipality and the Westfries Museum, an institution dedicated to Hoorn’s local history. I’ll keep an anthropological and sociological spirit to all this, for example, by proposing strategies to widen the public discussion. I’ll also suggest a solution to the issue that stresses the importance of involving local communities.

Coen’s Trail (2011-2012)

In the 21st century, the politics of immigration intensified and a new wave of nationalism that “re-invented today’s Dutch national identity” (Grever and Legêne 2023: 37-38; Macdonald 2013: 169-170) began rising. Increasingly more people bought into the narrative that the Netherlands is going through an “identity crisis” where things like its historical achievements, as well as ways to remember them (think of tangible heritage), are being threatened, especially by foreign presences (think of immigrants) (Kešić et al. 2022: 1345). As all this unfolded, rebellious acts towards Coen’s statue rose. A notable case was in 2011 when a petition collected 297 signatures from the 70,000-plus inhabitants of Hoorn in favor of relocating the statue to the Westfries Museum (van Engelenhoven 2022: 84). Ironically, a crane from a nearby construction site accidentally knocked the statue off shortly after. This put extra pressure on Hoorn’s municipal council. In the end, it decided to restore the statue, though it did replace the monument’s old plaque with one that is more critical of Coen. Shortly after, to facilitate the debate surrounding the monument, the Westfries Museum organized an exhibition that replicated a trial. Two historians acted as “expert witnesses” discussing Coen’s legacy in front of a “judge”. They concluded that the statue should remain on its plinth. Although this might seem like an impartial exhibition with a democratic outcome, there are many flaws.

First of all, the museum approached the debate surrounding the statue opportunistically by starring Maarten van Rossem as the “judge”, a “celebrity-historian” known in the academic sphere but outside too, commodifying the debate. Using van Rossem attracted a vast public. To add to this, the topic at hand was turned into a gossip-like one as the museum published a glossy magazine titled De Coen! Geroemd en verguisd (The Coen! Famed and reviled) to promote the exhibition. This generates a light-hearted tone around the debate, which in turn creates an emotional distancing from Coen’s wrongdoings and a lack of engagement with both its consequences and the arguments of Coen’s detractors. Another flaw is how the exposition’s experts were all three white Dutch men with no Indonesian background, depriving the event of any diversity. The trial’s verdict ended up being that Coen’s actions must be set in their historical context and could not be judged according to contemporary moral standards (van Engelenhoven 2022: 93). Because of this, no point was seen in removing the statue. Following this conclusion, most of the public also voted to keep the statue.

But the Westfries Museum is not the only one treating the subject lightheartedly. Hoorn’s municipality used the same formula to justify its decision to restore Coen’s statue after the crane incident. For example, some councilors have used endearing terms towards Coen, like “our rascal” (Johnson 2013: 7), while also saying that, despite his brutal actions, the benefits he brought to the Netherlands essentially outweigh them. And just like the Westfries, the municipality also argues that it’s unfair to judge Coen’s actions harshly through today’s lenses.

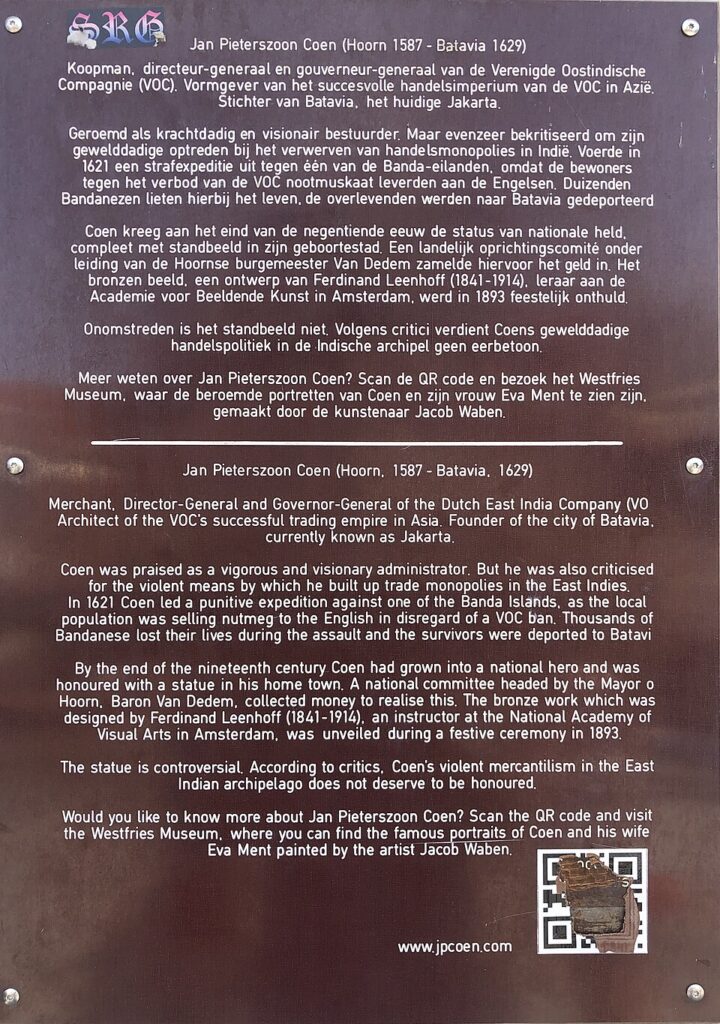

The “shrugging off” of Coen’s wrongdoings is also seen with the municipality’s updated plaque on the statue’s pedestal (see Figure 3). Though it adopts a somewhat critical stance towards Coen, it’s also filled with euphemisms. It refers to the Banda massacre as a “punitive expedition”, essentially justifying the killing by arguing that it happened because the Bandanese violated a VOC trading ban (van Engelenhoven 2022: 82), not mentioning that such a ban had been forced on the local population. Also, anti-Coen folks are mentioned in a short sentence, making them seem like an “odd” and “triggered” minority in Hoorn, putting into question their stance. The sentence also suggests that criticism has only been a recent phenomenon when, in reality, it can be traced back to the statue’s inauguration. Although activists have pointed out the biased plaque content, the inscription remains on the pedestal to this day. Something else to mention is that a QR code is displayed on the plaque, which leads to the “voicemail” of Coen, played by an actor. Here, users can express their opinions on his deeds and Hoorn’s monument. Although it’s arguably an engaging initiative by the museum, “it is doubtful whether a one-way possibility of expressing one’s opinion to a fake voicemail account with a prerecorded message from a voice actor is really all that interactive” (van Engelenhoven 2022: 103). You could also argue that without an explicit purpose, collecting opinions through Coen’s voicemail risks being a gimmick in line with the commodification of the issue blamed on the trial and exhibition. Not only that, but sending a voicemail to “personally connect” with the Governor-General makes it less likely for the public to take a moral stance towards the matter, similarly to the trial-exhibition’s case. In the end, then, the museum might not be as objective and impartial as we were meant to think it was. Van Engelenhoven refers to “repressive tolerance” here, a term developed by philosopher Herbert Marcuse, which refers to a tolerance that accepts the status quo and the attitude, opinions and practices of the majority even though they cause harm to minorities. Rather than challenging social oppression, such “tolerance” perpetuates it (Marcuse in van Engelenhoven 2022: 88). Unfortunately, the museum’s position in this Coen debate hasn’t changed much since the 2010s.

Coen’s Monument in the Debate about the Dutch Colonial Legacy (2020-2025)

George Floyd’s murder in 2020 triggered a new wave of decolonial protests across some Western countries, where colonial tangible heritage has been targeted, notably through graffiti that says things like “genocide”, as seen on Coen’s plinth (see Figure 2). Quite a few criticize these acts, considering them vandalistic, further creating polarization between critics and supporters of Coen’s monument and encouraging an “us” versus “them” mentality (Blok and Drieënhuizen 2020). At the same time, though, the increase in protests against colonial heritage, including against Coen’s statue in the Summer of 2020 (see Figure 4), has been beneficial for bringing back to life discussions on the monumentalization of Coen, including at a national level. Take the example in 2020, when Westfries Museum director Ad Geerdink (see Figure 5) stated on the institution’s website that the Westfries still aims to take “a neutral position in this discussion”, taking over “the role of helping anyone who wants to determine a position in the debate by providing information” (Kuiper 2021: 8). In an interview, he repeated that the best solution would be to add a new context to the statue to free it from any celebratory meaning (ibid.). But Mr. Geerdink doesn’t elaborate any further. He just added that this whole Coen controversy is part of a bigger talk on how the Netherlands deals with its colonial past. In this regard, the website of Historic England, a public body devoted to promoting projects in the field of cultural heritage, notes how the museum recognized “that its work to date on the Netherlands’ colonial past has overlooked the people who suffered its impact […] and is working to address this gap” (Historic England s.a.). Having this in mind, the next sentence might surprise you, since Historic England writes that the museum “is exploring ways of giving those people a voice while retaining a sense of neutrality” (ibid.). But isn’t it the absence of Indonesian voices that is weakening the museum’s “sense of neutrality”?

In 2021, the Westfries tried to make up for this lack of inclusivity by organizing a virtual exposition called Pala – Nutmeg tales of Banda on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of the Banda massacre. Since it took place during COVID-19, the exhibition was online in collaboration with 54 activists and scholars from different disciplines and various cultural backgrounds, including from Indonesia and the Moluccas, i.e., the province that the Banda Islands are part of. The narration was multimedial and multifaceted, with Mr. Geerdink publishing an article on the exposition’s site where he describes the massacre as a genocide without downplaying Coen’s responsibility by setting it in the historical context. However, when writing about Coen’s statue, he states that today it “functions mainly as an accusation against the ‘Butcher of Banda’. Thus, the monument has inadvertently become one of the bearers of the memory of the genocide on Banda” (Geerdink s.a.). He also mentions the opinion of Iswanto Hartono (see Figure 6), an Indonesian artist, who believes that having monuments linked to the colonial past lying around the Netherlands shouldn’t really matter anymore. By putting in evidence this bold take, Geerdink seems to suggest that we live in a post-colonial world where the Governor-General’s statue has essentially lost its “title” as a controversial monument. Unfortunately, the heated, ever-more polarized debate surrounding it points to a different reality. Once again, such a stance downplays the arguments of those supporting the statue’s removal, essentially siding with the status quo.

There’s also some educational material on Coen belonging to the museum that can be questioned. For example, in a lesson plan aimed at secondary classes, updated in 2024, the VOC is euphemistically presented as a “business company” and the Banda massacre is barely mentioned. To add to this, it’s stated that the monument “has been there for over 100 years. The statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen is almost an integral part of the Roode Steen in Hoorn. Yet some would rather see him go, portraying those who support his statue’s removal as a bitter and angry minority, arguably. The museum also has a series of podcasts aimed at providing Hoorn visitors with information about its main monuments. Here, Coen’s wrongdoings are discussed more straightforwardly, but the tone is still light-hearted. What’s even odder is the fact that the tone becomes almost humorous when one of the podcast speakers mentions “Don’t mess with Coen!” after going over the Banda massacre. Here, we can once again see the commodification of the topic that was present in the 2011 trial-exhibition.

Today, the statue’s removal is still an option since the municipality failed to decide on the removal in 2022, as had been originally established (DutchNews 2024). And the Westfries Museum, which has tried to use an innovative approach in its initiatives concerning Coen’s monumentalization and some degree of openness in considering critical feedback, has ultimately shown a lack of transparency and even intellectual honesty about its position. So, where can we go from here?

Conclusion – a Bottom-up Approach

Volchevska-Verbrugge (2024: 29) notes that heritage is often managed through “top-down” approaches where authorities, rather than local communities, take the lead. This is basically the case with Coen’s monument in Hoorn, even though the voting procedure was set up in 2012 on the occasion of Coen’s “trial”. In fact, the public who voted after the trial’s verdict was being influenced, more than informed, by the experts. Such an approach towards heritage, which may turn out to be elitist, “can neglect the actual impact on the ground” since it leaves little local community input (Zhang 2022: 46). However, in recent years, there has been a rise in critical heritage studies, which advocates for a “bottom-up” approach, where local communities are those who take charge of matters, as well as NGOs and activists, rather than authorities. This includes Poulios’ discussion on preservation that concerns “heritage as a process” (Poulios 2010: 181), i.e., heritage should be seen as an ongoing, dynamic process rather than a static set of values or physical assets to be preserved. Such a grassroots approach encourages heritage communities to seek more inclusive and sustainable management pathways, something UNESCO deemed important to start advocating for in management plans “if the heritage resources are to be sustained into the future” (Logan 2015: 257). This movement that emphasizes the role of communities in shaping heritage over time is promising for the Coen debate, but because of the polarization surrounding this discussion, communication strategies must be carefully weighed. Actions of “affective activism” aiming to provoke moral or even physical disgust toward monuments, like spray painting or smearing them with repellent substances, were effective in cases like Cecil Rhodes’ statue in Cape Town (Knudsen and Andersen 2019), but in the case of Coen’s statue, they’ve been counterproductive. This is because of the affectionate ties of many Hoorn inhabitants toward the monument and its central place, physical and metaphorical, within the community. Maybe, then, a better solution would be to “reframe” the monument, a concept proposed by Knudsen and Kølvraa (2020). To do this, we must recontextualize colonial heritage by adopting a critical stance and giving it a different meaning and purpose (ibid.: 11). Having an updated framework challenges rigid views of heritage, by seeing it as part of a contested cultural and political process (Yunis et al. 2024: 4). We could reframe by reflecting on how celebrating a controversial historical figure can shape the present and future identity of a community. The Westfries Museum can help out by bringing to the public space, in front of Coen’s monument, the voices of Indonesian historians, artists and citizens heard in the Pala – Nutmeg tales of Banda online exhibition. These voices narrate how the colonial past still affects the present. Like this, the museum can maintain its commitment to recontextualize the statue more convincingly, where a sense of tolerance is fostered that, as Marcuse would probably argue, grants anti-Coen protesters’ opinions the space and attention needed to shift dominant narratives.

Bibliography

Articles

Blok, Gemma and Caroline Drieënhuizen.

2020 ‘Coen hoort bij Hoorn’. Emoties rond een omstreden standbeeld. Open

Universiteit. https://www.ou.nl/-/jan-pieterszoon-coen, accessed on 7 August

2025.

DutchNews.

2024 Hoorn delays decision on removing controversial statue. DutchNews.

https://www.dutchnews.nl/2024/02/hoorn-delays-decision-on-removing-controver

sial-statue/, accessed on 7 August 2025.

Geerdink, Ad

s.a. Banda, the Loud Echo of a Massacre. PALA – Nutmeg Tales of Banda.

https://pala.westfriesmuseum.nl/echo/echo-article/?lang=en, accessed on 12

May 2025.

Grever, Maria and Susan Legêne

2023 Histories of an Old Empire: The Ever-Changing Acknowledgement of Dutch

Imperialism as a Present Past. In: Ander Delgado and Andrew Mycock (eds.),

Conflicts in History Education in Europe: Political Context, History Teaching, and

National Identity. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing. Pp. 27-48.

Grever, Maria

2025 Traces of Existence: Public Monuments and the Dead. Rethinking History 1-21.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2025.2470486.

Historic England.

s.a. Case Study: the ‘Coen Case’, Westfries Museum, Hoorn, Netherlands. Historic

England.

https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/planning/contested-heritage/reinterpreting-h

eritage/case-study-the-coen-case/, accessed on 7 August 2025.

Johnson, Lisa

2013 Renegotiating Dissonant Heritage: The Statue of J.P. Coen. International Journal

of Heritage Studies 20(6): 583-598. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2013.818571.

Kešić, Josip, Sammy C. Frenkel, Isabel Speelman and Jan Willem Duyvendak.

2022 Nativism and Nostalgia in the Netherlands. Sociological Forum 37(1): 1342-1359.

https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12841.

Knudsen Britta Tim and Casper Andersen.

2019 Affective politics and colonial heritage, Rhodes Must Fall at UCT and Oxford.

International Journal of Heritage Studies 25(3): 239-258.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.148113.

Knudsen, Britta Tim and Christoffer Kølvraa.

2020 Affective Infrastructures of Re-emergence? Exploring Modalities of Heritage

Practices in Nantes. Heritage & Society 13(1-2): 10-31.

https://doi.org/10.1080/2159032X.2021.1883981.

Kuiper, Bram.

2021 Here Stands Our Mladic: An Analysis of the Debate surrounding the Statue of

Jan Pieterszoon Coen in Hoorn between 2011 and 2020 [Bachelor’s thesis,

Universiteit Utrecht]. Utrecht University. https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/39002.

Logan, William

2015 Whose heritage? Conflicting narratives and top-down and

bottom-up approaches to heritage management in Yangon, Myanmar. In: Sophia

Labadi and William Logan (eds.), Urban Heritage, Development and

Sustainability. Routledge. Pp. 256-273. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315728018-17.

Macdonald, Sharon.

2013 Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. New York: Routledge.

Marcuse, Herbert.

1970 Repressive Tolerance. In: Robert Paul Wolff, Barrington Moore Jr. and Herbert

Marcuse (eds.), A Critique of Pure Tolerance. Beacon Press. Pp. 81-123.

Poulios, Ioannis

2010 Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage

Conservation. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 12(2):

170-185. https://doi.org/10.1179/175355210X12792909186539.

Van Engelenhoven, Gerlov

2022 Articulating Postcolonial Memory Through the Negotiation of Legalities: The

Case of Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s Statue in Hoorn. Law, Culture and the

Humanities 20(2): 273-290. https://doi.org/10.1177/17438721231179132.

Volchevska-Verbrugge, Biljana.

2024 The Symbolic Potential of the Past: Political Crises, Memory Politics, and

Europeanization in Southeastern Europe – the Case of North Macedonia

[doctoral thesis, Universiteit Utrecht]. Utrecht University.

https://doi.org/10.33540/2598.

Westfries Museum.

2024 Dossier Coen (Educatief Programma) Westfries Museum. Westfries Museum.

https://westfriesmuseum.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Dossier-Coen-2.pdf,

accessed on 7 August 2025.

Yunis, Alia, Robert Parthesius and Niccolò Acram Cappelletto.

2024 Future Stories in the Global Heritage Industry. Routledge.

Zhang, Lingran

2022 Towards a Better Approach: A Critical Analysis of Heritage

Preservation Practices. Open Journal of Social Sciences 10(5): 43-54.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2022.105005.

Images

Art World Database.

2022 Iswanto Hartono. Art World Database.

https://artworlddatabase.com/portfolio/iswanto-hartono/, accessed on 11 August

2025.

Dewnarain, Jerry

2021 Banda; The Genocide of Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Werkgroep Caraïbische

Letteren. https://werkgroepcaraibischeletteren.nl/banda-de-genocide-van-jan-pieterszoon-c

oen/, accessed on 15 May 2025.

EWmagazine.nl

2020 Ad Geerdink: ‘In de geschiedenis is niks voor eeuwig’. EWmagazine.nl.

https://www.ewmagazine.nl/nederland/achtergrond/2020/03/ad-geerdink-in-de-ge

schiedenis-is-niks-voor-eeuwig-198635w/, accessed on 11 August 2025.

Historic England.

s.a. Case Study: the ‘Coen Case’, Westfries Museum, Hoorn, Netherlands. Historic

England.

https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/planning/contested-heritage/reinterpreting-h

eritage/case-study-the-coen-case/, accessed on 7 August 2025.

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

2025 Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Pieterszoon_Coen, accessed

on 10 August 2025.

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

2025 Statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standbeeld_van_Jan_Pieterszoon_Coen, accessed

on 16 May 2025.