Written by Léa Lydie De Bruycker

Authenticity is a notion that is both highly codified and deeply ambivalent. In this article, we review the history and the progressive complexifying of the concept, as its use globalizes and spreads as a theoretical tool in the fields of Museums & Heritage Studies.

This article will examine the concept of authenticity in heritage studies, departing from its traditional grounding in material culture, epitomized by frameworks like the Venice Charter (1964), to explore how debates around intangible practices, subjective experiences, and evolving cultural values have reshaped its meaning. By foregrounding tensions between preservation of physical heritage and the dynamism of living traditions, I argue that authenticity is not a fixed attribute, but a contested terrain shaped by power, perception, and participatory engagement.

a. The Venice Charter (1964)

The concept was first formalized in the Venice Charter during the 2nd Congrès international des architectes et des techniciens des monuments historiques, in 1964.

Download the Charter in French (original version)

Authenticity is introduced in the preamble, basically as the value that grants a monument its status as a material witness to the richness of past civilizations:

“Charged with a spiritual message from the past, the monumental works of peoples remain, in present life, as living witnesses of their age-old traditions. Humanity, becoming increasingly aware of the unity of human values, regards them as a common heritage and, with respect to future generations, acknowledges a shared responsibility for their preservation. It must pass them on in all the richness of their authenticity.”

(Personal translation)

It is also addressed in Article 9, in the section of the Charter dedicated to the restoration practices for monuments:

“Restoration is a process that must retain an exceptional character. Its aim is to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historical values of the monument, and it is based on respect for original material and authentic documents. […] Restoration must always be preceded and accompanied by an archaeological and historical study of the monument.”

(Personal translation)

It is stipulated in those lines that authenticity, as an aesthetic and historical value, is a matter of expertise: competent authorities (archaeologists, historians) must be consulted to guarantee that the monument’s authenticity is preserved during a restoration campaign.

This understanding of authenticity as the product of an expert process is also seen in the criteria examined for inscribing a monument or site on the UNESCO World Heritage list (protection, management, authenticity, and integrity). To be inscribed under criteria I (“represent a masterpiece of human creative genius”) or VI (“be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance”), a monument must be authenticated by an expert or panel of experts who justify its designation as heritage.

b. The Nara Declaration (1994)

It should be noted that back in the 1960s, when the Venice Charter was adopted, institutionalized heritage remained largely a Western concern. Indeed, among the 23 participants in the commission drafting the Charter, only 3 came from non-European countries. Therefore, the previous considerations on authenticity became unsuitable when applied to other cultural contexts.

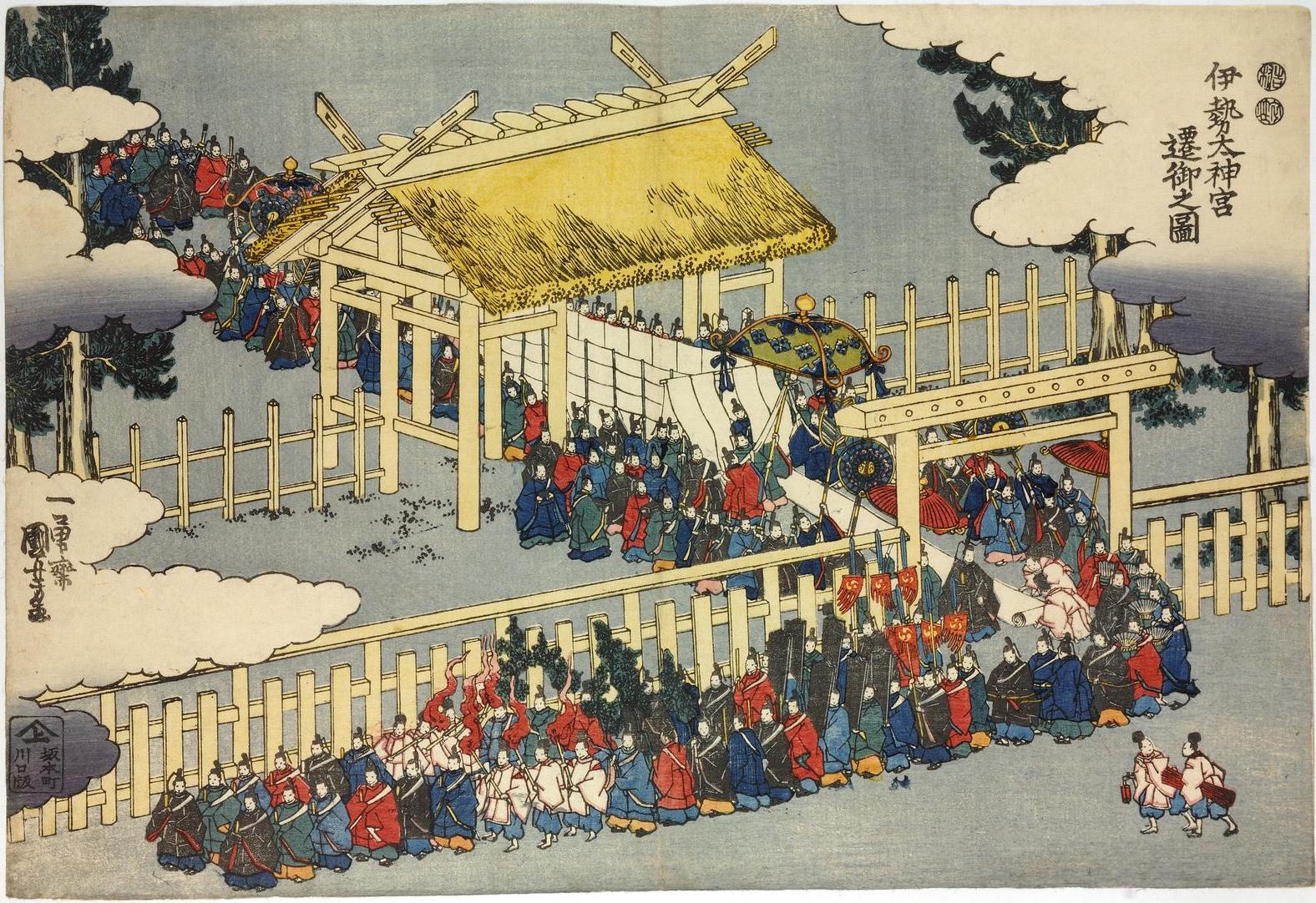

A representative case study is the problem of Japan’s built heritage’s restoration. In Japanese conservation tradition, the relevance of a called-so monument relies less on original materiality (such as old stones or wood) and more on the transmission of know-how and the persistence of the spirit of the place. For example, the Ise Jingū Shrine was rebuilt every 20 years since it was built, using the same traditional techniques. Therefore, the building never stays authentic, in a material sense, but its ritual use and the craftsmen’s skills was rigorously preserved for centuries.

Sengu ceremony when it was rebuilt in 1849. By Hiroshige, 1849 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

According to Western standards and the conception of authenticity as written in Article 9 of the Venice Charter, such reconstruction over time might be considered a systematic loss of authenticity. Yet, in this case, true authenticity lies in cultural and ritual continuity, and not in material substance. In the 1990s, Japan, drawing on its growing involvement in international debates, played a role of mediator to open real intercultural discussions on authenticity. This resulted in the adoption of the Nara Declaration, drafted by a committee of 45 international experts under the leadership of UNESCO, ICOMOS, and ICCROM:

Download the Declaration in English

“4. In a world affected by the forces of globalization […], the primary contribution of considering authenticity in cultural heritage conservation is also to respect and highlight all facets of humanity’s collective memory.”

(Personal translation)

“13. Depending on the nature of the monument or site and its cultural context, judgments about authenticity are related to a variety of sources of information. These include design and form, materials and substance, use and function, tradition and techniques, location and setting, spirit and feeling, original state and historical development. These sources may be internal to the work or external to it. Using these sources allows the cultural heritage to be described in its specific artistic, technical, historical, and social dimensions.”

(Personal translation)

This declaration has a performative effect on worldwide heritage management. In 1997, the UNESCO decided to re-examine criteria related to the inscription of cultural properties and authenticity. The Nara Declaration was integrated into the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (pp. 95-98):

Download the last version of Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention

“The World Heritage Committee examined the report of the Nara meeting on Authenticity at its 18th session. […] Subsequent expert meetings have enriched the concept of authenticity in relation to the World Heritage Convention.”

c. Renegotiating of a concept: the example of tourism studies

Although these declarations helped formalize the definition of authenticity within an operational framework, in theoretical Heritage and Museum Studies research, the concept has become increasingly ambiguous as it expands into new fields.

One of the most cited articles in academic papers is “Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience” (Wang, 1999). In this article, the author aims to reconfigure the concept of authenticity. Indeed, the Venice Charter and the Nara Declaration define authenticity as intrinsic, an objective quality of monuments, practices, and know-how. Ning Wang, for his part, asserts that, in the case of tourism, the experience of authenticity cannot be reduced to a technical evaluation of the material or historical truth of a heritage piece; it also involves the living experience of the receptor.

The author identifies three forms of authenticity:

- Objective authenticity – The traditional form of the concept, based on the idea of a acknowledged authentic original object or monument;

- Constructive authenticity, influenced by social constructivism, postulates that authenticity is constructed by discourses, contexts, and collective beliefs. Here, it is the tourists’ perceptions and expectations that shape the authenticity;

- Existential authenticity refers to an inner feeling of authenticity, a personal and subjective experience lived by the tourist, regardless of the nature of the tourist object. Authenticity no longer resides in the heritage but in the subject’s relation to themselves.

This approach radically complicates normative definitions of authenticity. Where the Venice Charter and the Nara Declaration attempt to stabilize authenticity through universal criteria, Wang shows that in tourism, authenticity is both situated and subjective:

“The key point at issue is, however, that authenticity is not a matter of black or white, but rather involves a much wider spectrum, rich in ambiguous colors. That which is judged as inauthentic or staged authenticity by experts, intellectuals, or elite may be experienced as authentic and real from an emic perspective.”

(p.353)

d. Documenting authenticity: a paradigm shift

These previous considerations on authenticity as multifaceted and multisubjective implies a methodological paradigm shift for researchers in Museums & Heritage Studies. To understand what authenticity consists of in a monument, object, site, or know-how, one cannot rely solely on expert opinion: it is necessary to collect the various discourses and practices of a wide range of stakeholders – tourists, residents, managers, guides, media, etc. – who orbit around the same heritage and bring different sensitive perspectives to it. It is in these interactions, negotiations, and even conflicts of meaning that the authenticity of heritage is constructed in each context.

Thus, the study of authenticity requires an inclusive, multilayered, and multi-situated approach, attentive to practices, discourses, and representations of the object, rather than the assessment of whether fixed criteria are met or not. Approaching the mechanisms of authenticity construction in this way also allows researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the power, legitimacy, and identity issues that intersect a heritage site, and often extends widely beyond its borders.

References & further reading…

Brenna, B., Christensen, H. D., & Hamran, O. (Éds.) Museums as Cultures of Copies: The Crafting of Artefacts and Authenticity (p. 225-239). Routledge.

Dai, T., Zheng, X., & Yan, J. (2021). Contradictory or aligned? The nexus between authenticity in heritage conservation and heritage tourism, and its impact on satisfaction. Habitat International, 107, 102307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102307

Gao, Q., & and Jones, S. (2021). Authenticity and heritage conservation: Seeking common complexities beyond the ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ dichotomy. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(1), 90106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1793377

Jokilehto, J. (2021). Observations on Concepts in the Venice Charter. Conversaciones…, 11, 353363. https://portal.amelica.org/ameli/journal/317/3173864024/html/

Su, J. (2021). A Difficult Integration of Authenticity and Intangible Cultural Heritage? The Case of Yunnan, China. China Perspectives, 2021/3, Article 2021/3. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.12223

Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

Wood, B. (2020). A Review of the Concept of Authenticity in Heritage, with Particular Reference to Historic Houses. Collections, 16(1), 833. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550190620904798